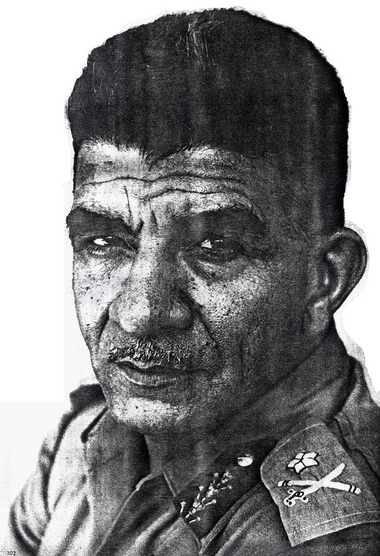

Photos of Gamal Abdel Nasser filled yesterday’s newspapers with articles commemorating his July 23rd coup (or revolution, depending on your political inclinations). But one man was again absent from the yearly love fest: General Mohamed Naguib, Egypt’s first president and the leader of the 1952 movement.

In 1949, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, then a mid-level military officer and founder of the Free Officer’s Movement, invited Naguib to join and lead the group. They needed an older, more recognised name to act as leader.

Naguib was the perfect man for the job. He had been one of the very few military men seen as a hero in the aftermath of the 1948 war, known inside military circles for being a polite, pious and cultured man.

Following the Arab defeat in the 1948 war, Naguib became even more disillusioned with the monarchy, top military brass and political elites whose corruption he blamed for the defeat.

He submitted his resignation twice to King Farouk, once after the 4 February, 1942 standoff at Abdeen Palace when British tanks surrounded the royal palace and the British forced the king to appoint the Wafd Party’s Moustafa El-Nahas as prime minister and ask him to form a Wafd cabinet.

Feeling humiliated at the extent of British intervention in Egyptian affairs, Naguib wrote to the King saying, “Since the army was not called upon to defend Your Majesty, I am ashamed to wear this uniform and ask your permission to resign.”

Farouk denied his request.

On 6 January, 1952 Naguib, backed by the Free Officers, was elected as head of the Officer’s Club, defeating Hussein Serri Amer who was nominated by the king, unprecedented as the king’s nominees always won the post. In response, Farouk dissolved the club’s executive board.

Farouk’s move, and the Cairo Fires of 26 January, as well as the fact that the government was close to arresting the Free Officers after discovering their names and plans, led to Nasser changing his plan to launch the coup in 1955 and bringing it forward to 23 July, 1952.

Naguib was immediately declared Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces in order to keep the military loyal and the Free Officers formed the Revolutionary Command Council with Naguib as chairman and Nasser as vice chairman.

In September 1952 the RCC appointed Naguib as prime minister and member of Fouad’s regency council. Nasser became deputy prime minister and minister of interior, preferring to work in the background at the time.

Almost a year after the officer’s coup, the RCC abolished the monarchy and declared Egypt a republic in September 1953. Naguib was proclaimed president alongside his roles as prime minister, RCC chairman and commander-in-chief, effectively making him Egypt’s strongman leading a government composed of mostly military men but only as a figurehead.

Naguib began to clash with the other RCC members, led by Nasser, over the revolution’s goals and how to implement them.

“At the age of 36, Abdel-Nasser felt that we could ignore Egyptian public opinion until we had reached our goals, but with the caution of a 53-year-old, I believed that we needed grassroots support for our policies, even if it meant postponing some of our goal,” Naguib wrote in his book I Was President of Egypt.

On February 22, 1953 Naguib submitted his resignation to the RCC. On the 25th they released a statement saying they removed him from his position because he asked for dictatorial powers. Nasser accused him of being a Muslim Brotherhood sympathizer involved in a plot to overthrow the RCC and took over as prime minister and RCC chairman with the presidency remaining vacant.

The next day mass protests broke out against the decision, calling for Naguib to be reinstated. The RCC issued a statement reappointing Naguib as president. Naguib would become even more of a figurehead with the title of president largely ceremonial.

Naguib’s final stand would come one month later in the March 1954 Crisis. Upon reassuming the presidency, Naguib called for a meeting of the Constituent Assembly on March 5 and tasked it with drafting a new democratic constitution.

On March 28 massive protests broke out in front of parliament, the presidential palace and the State Council against democracy and political parties chanting “no to parliament or parties” and “down with democracy and freedom.” One of the main organisers of the protests, transport union head Sawy Ahmed Sawy, later admitted receiving EGP 4,000 from Nasser in return for staging the protests. The RCC responded by cancelling Naguib’s decisions who responded by submitting his resignation only for Nasser to reject it.

On 14 November, 1954, Mohamed Naguib headed from his house to the presidential office only to notice that the military police were not giving him a military salute. As he walked out of his car and headed toward the building, he was met with three officers and 10 soldiers carrying rifles. He yelled that their actions would cause a battle with the republican guard. Two military policemen followed him up the stairs and said they had permission from the head of the presidential guard.

Naguib called Nasser and informed him of the situation and Nasser said he would send Amer, the military’s commander-in-chief, to deal with the situation. Amer arrived shortly and informed Naguib that the RCC has decided to remove him as president. Naguib answered that he did not want to resign as to not be responsible for civil strife.

Naguib spent the next 30 years under house arrest in Zeinab Al-Wakeel’s (El-Nahas’s wife) villa. He was released in 1974 by then-President Anwar El-Sadat and died in 1984. His name would not be mentioned in school history books before the late 1990s. He suffered mistreatment and insult in his solitary prison where he wrote his book I Was President of Egypt.

“I wish I had not returned [to public life].” Naguib wrote. “Everyone was in a state of bitterness because of defeat and occupation. All they talked of was pain and lack of hope at expelling the Israeli occupation. In addition to that there were the victims of the revolution, those who were just released from prisons and suffered torture. And even those who were not imprisoned felt fear and humiliation. I then realised how much of a crime the revolution committed against the Egyptian citizen, who lost his freedom, dignity, land, his troubles doubled, sanitation was a mess, water was scarce, morals decayed, and the people were lost.”